bug

( n.)

An unwanted and unintended property of a program or piece of

hardware, esp. one that causes it to malfunction. Antonym of

{feature}. Examples: "There's a bug in the editor: it writes things

out backwards." "The system crashed because of a hardware bug." "Fred

is a winner, but he has a few bugs" (i.e., Fred is a good guy, but he

has a few personality problems).

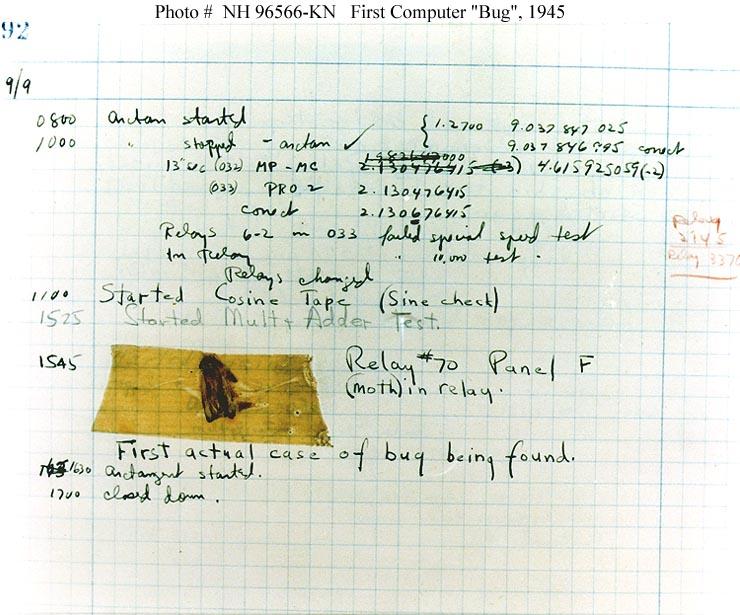

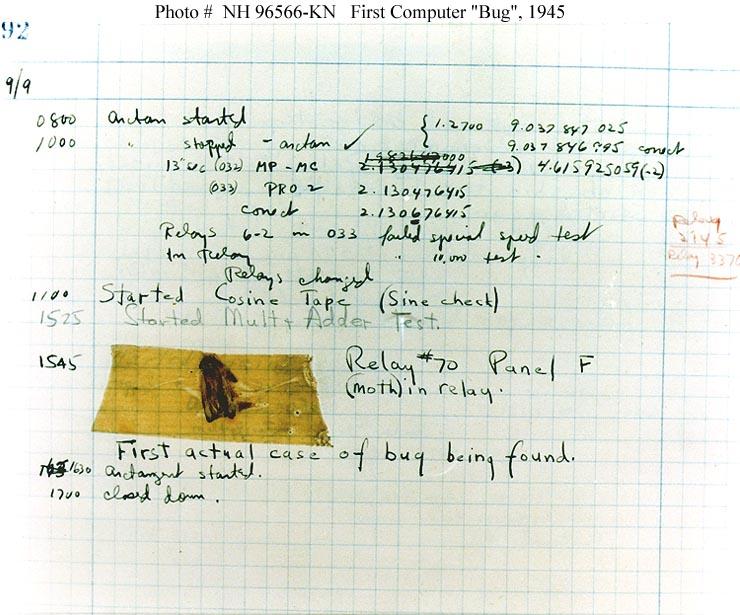

Historical note: Admiral Grace Hopper (an early computing pioneer

better known for inventing {COBOL}) liked to tell a story in which a

technician solved a {glitch} in the Harvard Mark II machine by

pulling an actual insect out from between the contacts of one of its

relays, and she subsequently promulgated {bug} in its hackish sense

as a joke about the incident (though, as she was careful to admit,

she was not there when it happened). For many years the logbook

associated with the incident and the actual bug in question (a moth)

sat in a display case at the Naval Surface Warfare Center (NSWC). The

entire story, with a picture of the logbook and the moth taped into

it, is recorded in the Annals of the History of Computing, Vol. 3,

No. 3 (July 1981), pp. 285--286.

The text of the log entry (from September 9, 1947), reads "1545 Relay

#70 Panel F (moth) in relay. First actual case of bug being found".

This wording establishes that the term was already in use at the time

in its current specific sense -- and Hopper herself reports that the

term bug was regularly applied to problems in radar electronics

during WWII.

The `original bug' (the caption date is incorrect)

Indeed, the use of bug to mean an industrial defect was already

established in Thomas Edison's time, and a more specific and rather

modern use can be found in an electrical handbook from 1896 (Hawkin's

New Catechism of Electricity, Theo. Audel & Co.) which says: "The

term `bug' is used to a limited extent to designate any fault or

trouble in the connections or working of electric apparatus." It

further notes that the term is "said to have originated in quadruplex

telegraphy and have been transferred to all electric apparatus."

The latter observation may explain a common folk etymology of the

term; that it came from telephone company usage, in which "bugs in a

telephone cable" were blamed for noisy lines. Though this derivation

seems to be mistaken, it may well be a distorted memory of a joke

first current among telegraph operators more than a century ago!

Or perhaps not a joke. Historians of the field inform us that the

term "bug" was regularly used in the early days of telegraphy to

refer to a variety of semi-automatic telegraphy keyers that would

send a string of dots if you held them down. In fact, the Vibroplex

keyers (which were among the most common of this type) even had a

graphic of a beetle on them (and still do)! While the ability to send

repeated dots automatically was very useful for professional morse

code operators, these were also significantly trickier to use than

the older manual keyers, and it could take some practice to ensure

one didn't introduce extraneous dots into the code by holding the key

down a fraction too long. In the hands of an inexperienced operator,

a Vibroplex "bug" on the line could mean that a lot of garbled Morse

would soon be coming your way.

Further, the term "bug" has long been used among radio technicians to

describe a device that converts electromagnetic field variations into

acoustic signals. It is used to trace radio interference and look for

dangerous radio emissions. Radio community usage derives from the

roach-like shape of the first versions used by 19th century

physicists. The first versions consisted of a coil of wire (roach

body), with the two wire ends sticking out and bent back to nearly

touch forming a spark gap (roach antennae). The bug is to the radio

technician what the stethoscope is to the stereotypical medical

doctor. This sense is almost certainly ancestral to modern use of

"bug" for a covert monitoring device, but may also have contributed

to the use of "bug" for the effects of radio interference itself.

Actually, use of bug in the general sense of a disruptive event goes

back to Shakespeare! (Henry VI, part III - Act V, Scene II: King

Edward: "So, lie thou there. Die thou; and die our fear; For Warwick

was a bug that fear'd us all.") In the first edition of Samuel

Johnson's dictionary one meaning of bug is "A frightful object; a

walking spectre"; this is traced to `bugbear', a Welsh term for a

variety of mythological monster which (to complete the circle) has

recently been reintroduced into the popular lexicon through fantasy

role-playing games.

In any case, in jargon the word almost never refers to insects. Here

is a plausible conversation that never actually happened: "There is a

bug in this ant farm!" "What do you mean? I don't see any ants in

it." "That's the bug."

A careful discussion of the etymological issues can be found in a

paper by Fred R. Shapiro, 1987, "Entomology of the Computer Bug:

History and Folklore", American Speech 62(4):376-378.

[There has been a widespread myth that the original bug was moved to

the Smithsonian, and an earlier version of this entry so asserted. A

correspondent who thought to check discovered that the bug was not

there. While investigating this in late 1990, your editor discovered

that the NSWC still had the bug, but had unsuccessfully tried to get

the Smithsonian to accept it -- and that the present curator of their

History of American Technology Museum didn't know this and agreed

that it would make a worthwhile exhibit. It was moved to the

Smithsonian in mid-1991, but due to space and money constraints was

not actually exhibited for years afterwards. Thus, the process of

investigating the original-computer-bug bug fixed it in an entirely

unexpected way, by making the myth true! --ESR]

The `original bug' (the caption date is incorrect)

Indeed, the use of bug to mean an industrial defect was already

established in Thomas Edison's time, and a more specific and rather

modern use can be found in an electrical handbook from 1896 (Hawkin's

New Catechism of Electricity, Theo. Audel & Co.) which says: "The

term `bug' is used to a limited extent to designate any fault or

trouble in the connections or working of electric apparatus." It

further notes that the term is "said to have originated in quadruplex

telegraphy and have been transferred to all electric apparatus."

The latter observation may explain a common folk etymology of the

term; that it came from telephone company usage, in which "bugs in a

telephone cable" were blamed for noisy lines. Though this derivation

seems to be mistaken, it may well be a distorted memory of a joke

first current among telegraph operators more than a century ago!

Or perhaps not a joke. Historians of the field inform us that the

term "bug" was regularly used in the early days of telegraphy to

refer to a variety of semi-automatic telegraphy keyers that would

send a string of dots if you held them down. In fact, the Vibroplex

keyers (which were among the most common of this type) even had a

graphic of a beetle on them (and still do)! While the ability to send

repeated dots automatically was very useful for professional morse

code operators, these were also significantly trickier to use than

the older manual keyers, and it could take some practice to ensure

one didn't introduce extraneous dots into the code by holding the key

down a fraction too long. In the hands of an inexperienced operator,

a Vibroplex "bug" on the line could mean that a lot of garbled Morse

would soon be coming your way.

Further, the term "bug" has long been used among radio technicians to

describe a device that converts electromagnetic field variations into

acoustic signals. It is used to trace radio interference and look for

dangerous radio emissions. Radio community usage derives from the

roach-like shape of the first versions used by 19th century

physicists. The first versions consisted of a coil of wire (roach

body), with the two wire ends sticking out and bent back to nearly

touch forming a spark gap (roach antennae). The bug is to the radio

technician what the stethoscope is to the stereotypical medical

doctor. This sense is almost certainly ancestral to modern use of

"bug" for a covert monitoring device, but may also have contributed

to the use of "bug" for the effects of radio interference itself.

Actually, use of bug in the general sense of a disruptive event goes

back to Shakespeare! (Henry VI, part III - Act V, Scene II: King

Edward: "So, lie thou there. Die thou; and die our fear; For Warwick

was a bug that fear'd us all.") In the first edition of Samuel

Johnson's dictionary one meaning of bug is "A frightful object; a

walking spectre"; this is traced to `bugbear', a Welsh term for a

variety of mythological monster which (to complete the circle) has

recently been reintroduced into the popular lexicon through fantasy

role-playing games.

In any case, in jargon the word almost never refers to insects. Here

is a plausible conversation that never actually happened: "There is a

bug in this ant farm!" "What do you mean? I don't see any ants in

it." "That's the bug."

A careful discussion of the etymological issues can be found in a

paper by Fred R. Shapiro, 1987, "Entomology of the Computer Bug:

History and Folklore", American Speech 62(4):376-378.

[There has been a widespread myth that the original bug was moved to

the Smithsonian, and an earlier version of this entry so asserted. A

correspondent who thought to check discovered that the bug was not

there. While investigating this in late 1990, your editor discovered

that the NSWC still had the bug, but had unsuccessfully tried to get

the Smithsonian to accept it -- and that the present curator of their

History of American Technology Museum didn't know this and agreed

that it would make a worthwhile exhibit. It was moved to the

Smithsonian in mid-1991, but due to space and money constraints was

not actually exhibited for years afterwards. Thus, the process of

investigating the original-computer-bug bug fixed it in an entirely

unexpected way, by making the myth true! --ESR]

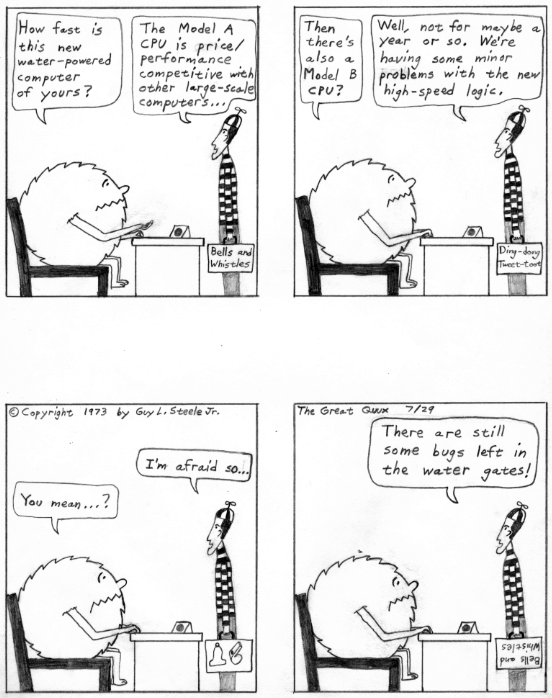

It helps to remember that this dates from 1973.

(The next cartoon in the Crunchly saga is 73-10-31. The previous

cartoon was 73-07-24.)

It helps to remember that this dates from 1973.

(The next cartoon in the Crunchly saga is 73-10-31. The previous

cartoon was 73-07-24.)

[glossary]

[Reference(s) to this entry by made by: {Bohr bug}{bug}{feature}{misbug}{off the trolley}{restriction}{TECO}{workaround}]

The `original bug' (the caption date is incorrect)

Indeed, the use of bug to mean an industrial defect was already

established in Thomas Edison's time, and a more specific and rather

modern use can be found in an electrical handbook from 1896 (Hawkin's

New Catechism of Electricity, Theo. Audel & Co.) which says: "The

term `bug' is used to a limited extent to designate any fault or

trouble in the connections or working of electric apparatus." It

further notes that the term is "said to have originated in quadruplex

telegraphy and have been transferred to all electric apparatus."

The latter observation may explain a common folk etymology of the

term; that it came from telephone company usage, in which "bugs in a

telephone cable" were blamed for noisy lines. Though this derivation

seems to be mistaken, it may well be a distorted memory of a joke

first current among telegraph operators more than a century ago!

Or perhaps not a joke. Historians of the field inform us that the

term "bug" was regularly used in the early days of telegraphy to

refer to a variety of semi-automatic telegraphy keyers that would

send a string of dots if you held them down. In fact, the Vibroplex

keyers (which were among the most common of this type) even had a

graphic of a beetle on them (and still do)! While the ability to send

repeated dots automatically was very useful for professional morse

code operators, these were also significantly trickier to use than

the older manual keyers, and it could take some practice to ensure

one didn't introduce extraneous dots into the code by holding the key

down a fraction too long. In the hands of an inexperienced operator,

a Vibroplex "bug" on the line could mean that a lot of garbled Morse

would soon be coming your way.

Further, the term "bug" has long been used among radio technicians to

describe a device that converts electromagnetic field variations into

acoustic signals. It is used to trace radio interference and look for

dangerous radio emissions. Radio community usage derives from the

roach-like shape of the first versions used by 19th century

physicists. The first versions consisted of a coil of wire (roach

body), with the two wire ends sticking out and bent back to nearly

touch forming a spark gap (roach antennae). The bug is to the radio

technician what the stethoscope is to the stereotypical medical

doctor. This sense is almost certainly ancestral to modern use of

"bug" for a covert monitoring device, but may also have contributed

to the use of "bug" for the effects of radio interference itself.

Actually, use of bug in the general sense of a disruptive event goes

back to Shakespeare! (Henry VI, part III - Act V, Scene II: King

Edward: "So, lie thou there. Die thou; and die our fear; For Warwick

was a bug that fear'd us all.") In the first edition of Samuel

Johnson's dictionary one meaning of bug is "A frightful object; a

walking spectre"; this is traced to `bugbear', a Welsh term for a

variety of mythological monster which (to complete the circle) has

recently been reintroduced into the popular lexicon through fantasy

role-playing games.

In any case, in jargon the word almost never refers to insects. Here

is a plausible conversation that never actually happened: "There is a

bug in this ant farm!" "What do you mean? I don't see any ants in

it." "That's the bug."

A careful discussion of the etymological issues can be found in a

paper by Fred R. Shapiro, 1987, "Entomology of the Computer Bug:

History and Folklore", American Speech 62(4):376-378.

[There has been a widespread myth that the original bug was moved to

the Smithsonian, and an earlier version of this entry so asserted. A

correspondent who thought to check discovered that the bug was not

there. While investigating this in late 1990, your editor discovered

that the NSWC still had the bug, but had unsuccessfully tried to get

the Smithsonian to accept it -- and that the present curator of their

History of American Technology Museum didn't know this and agreed

that it would make a worthwhile exhibit. It was moved to the

Smithsonian in mid-1991, but due to space and money constraints was

not actually exhibited for years afterwards. Thus, the process of

investigating the original-computer-bug bug fixed it in an entirely

unexpected way, by making the myth true! --ESR]

The `original bug' (the caption date is incorrect)

Indeed, the use of bug to mean an industrial defect was already

established in Thomas Edison's time, and a more specific and rather

modern use can be found in an electrical handbook from 1896 (Hawkin's

New Catechism of Electricity, Theo. Audel & Co.) which says: "The

term `bug' is used to a limited extent to designate any fault or

trouble in the connections or working of electric apparatus." It

further notes that the term is "said to have originated in quadruplex

telegraphy and have been transferred to all electric apparatus."

The latter observation may explain a common folk etymology of the

term; that it came from telephone company usage, in which "bugs in a

telephone cable" were blamed for noisy lines. Though this derivation

seems to be mistaken, it may well be a distorted memory of a joke

first current among telegraph operators more than a century ago!

Or perhaps not a joke. Historians of the field inform us that the

term "bug" was regularly used in the early days of telegraphy to

refer to a variety of semi-automatic telegraphy keyers that would

send a string of dots if you held them down. In fact, the Vibroplex

keyers (which were among the most common of this type) even had a

graphic of a beetle on them (and still do)! While the ability to send

repeated dots automatically was very useful for professional morse

code operators, these were also significantly trickier to use than

the older manual keyers, and it could take some practice to ensure

one didn't introduce extraneous dots into the code by holding the key

down a fraction too long. In the hands of an inexperienced operator,

a Vibroplex "bug" on the line could mean that a lot of garbled Morse

would soon be coming your way.

Further, the term "bug" has long been used among radio technicians to

describe a device that converts electromagnetic field variations into

acoustic signals. It is used to trace radio interference and look for

dangerous radio emissions. Radio community usage derives from the

roach-like shape of the first versions used by 19th century

physicists. The first versions consisted of a coil of wire (roach

body), with the two wire ends sticking out and bent back to nearly

touch forming a spark gap (roach antennae). The bug is to the radio

technician what the stethoscope is to the stereotypical medical

doctor. This sense is almost certainly ancestral to modern use of

"bug" for a covert monitoring device, but may also have contributed

to the use of "bug" for the effects of radio interference itself.

Actually, use of bug in the general sense of a disruptive event goes

back to Shakespeare! (Henry VI, part III - Act V, Scene II: King

Edward: "So, lie thou there. Die thou; and die our fear; For Warwick

was a bug that fear'd us all.") In the first edition of Samuel

Johnson's dictionary one meaning of bug is "A frightful object; a

walking spectre"; this is traced to `bugbear', a Welsh term for a

variety of mythological monster which (to complete the circle) has

recently been reintroduced into the popular lexicon through fantasy

role-playing games.

In any case, in jargon the word almost never refers to insects. Here

is a plausible conversation that never actually happened: "There is a

bug in this ant farm!" "What do you mean? I don't see any ants in

it." "That's the bug."

A careful discussion of the etymological issues can be found in a

paper by Fred R. Shapiro, 1987, "Entomology of the Computer Bug:

History and Folklore", American Speech 62(4):376-378.

[There has been a widespread myth that the original bug was moved to

the Smithsonian, and an earlier version of this entry so asserted. A

correspondent who thought to check discovered that the bug was not

there. While investigating this in late 1990, your editor discovered

that the NSWC still had the bug, but had unsuccessfully tried to get

the Smithsonian to accept it -- and that the present curator of their

History of American Technology Museum didn't know this and agreed

that it would make a worthwhile exhibit. It was moved to the

Smithsonian in mid-1991, but due to space and money constraints was

not actually exhibited for years afterwards. Thus, the process of

investigating the original-computer-bug bug fixed it in an entirely

unexpected way, by making the myth true! --ESR]

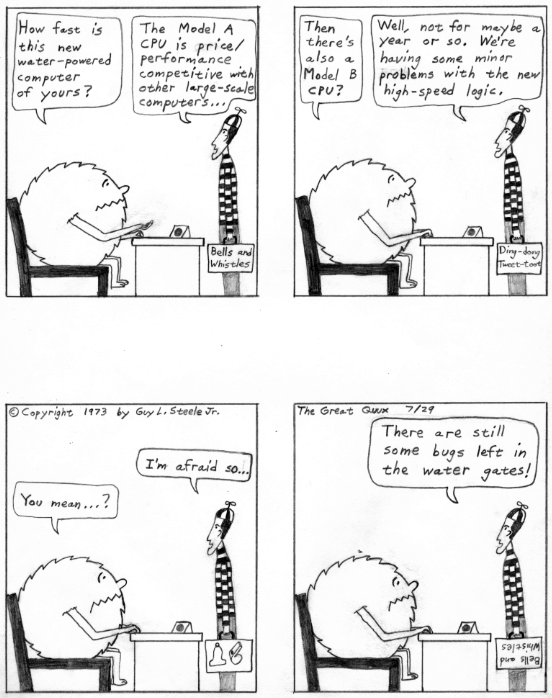

It helps to remember that this dates from 1973.

(The next cartoon in the Crunchly saga is 73-10-31. The previous

cartoon was 73-07-24.)

It helps to remember that this dates from 1973.

(The next cartoon in the Crunchly saga is 73-10-31. The previous

cartoon was 73-07-24.)